AKLEG Day 56: 'I don't want to teach on the Titanic.'

Turns out there may have been a reason the governor was trying to rush everything through with little to no scrutiny.

It’s Monday, Alaska.

Programming note: I’m sorry for the radio silence for the last week and change. I’ve been really under the weather, but I’m on the upswing for what should be an eventful week.

In this edition: It’s a big week in the Alaska Legislature. Thursday marks the deadline for the governor to fulfill his threat to veto the education bill unless the Legislature delivers a second education bill containing his $180 million study on teacher bonuses and changes that would take the local out of the local charter school system. A pair of Senate hearings highlighted how bad of an idea those asks are, but there have also been some closed-door meetings, so a lot could still happen. Before then, on Tuesday, legislators are headed into a joint session to review the governor’s expansive slate of power-consolidating executive orders. Some are so laughably bad that even governor-friendly Republicans are pointing out the flaws.

Current mood: 🤧

‘I don’t want to teach on the Titanic.’

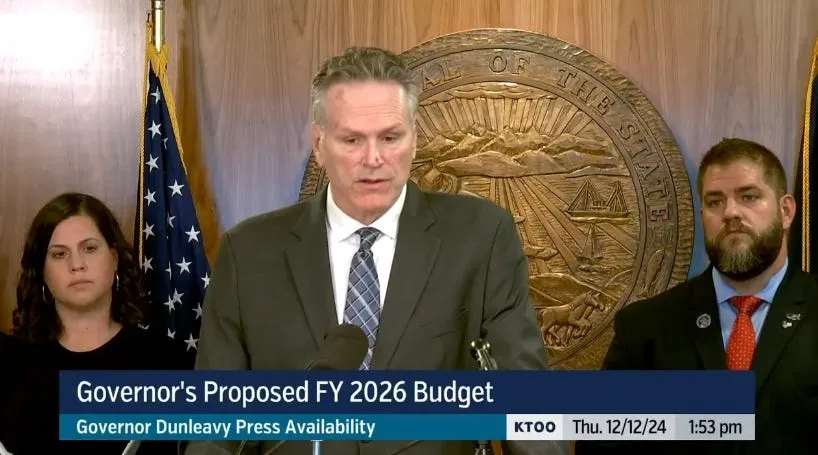

When Alaska Republican Gov. Mike Dunleavy stepped up to the microphone on Feb. 27 to deliver an hour-long rant on the Legislature’s recently passed Senate Bill 140—a landmark bill that includes the single most significant increase to the state’s baseline school funding system—he presented the solutions as simple and obvious.

Rather than a straightforward increase in school funding that would allow local districts to address their individual needs and budget challenges, the governor argued that the real solution to Alaska’s revolving door of teachers is bonuses ranging from $5,000 to $15,000 for the next three years. With a straight face, he insisted that young Alaskans would prefer to make a few car payments instead of having the generous pension he accrued as a teacher. He ranted and hollered at the subdued response to a study by a pro-charter researcher that found Alaska’s public charter schools fared well compared to other charter schools nationwide, insisting that it should be a cause for celebration if not a parade. Rather than understand why charters perform so well—a question not addressed by the study—or how those practices could be extended to all students, he demanded that the Legislature turn over the keys to the Board of Education (which is wholly appointed by the governor) without knowing how much it’ll cost or what, if any, standards there would be if the state could force local districts to open and operate new charters.

Get it all passed, he threatened, and he would let the original education bill that passed with the support of all but three legislators become law. Notably, even if the Legislature delivered on his request, he made no promises to fund the original education bill. Instead, he said it’d have to be a conversation later this year.

While there have been some closed-door talks between everyone on a deal, the only public-facing action on the governor’s demands hasn’t exactly painted them in the most flattering light. There may have been a reason the governor was trying to rush everything through with little to no scrutiny.

The Senate Education Committee held a pair of hearings last week on the teacher bonus study bill and the charter school expansion, which has never actually been introduced as legislation. (Meanwhile, the House Education Committee hadn’t met since mid-February due to infighting between its Republican co-chairs, depriving the governor of the one forum where he could get a less skeptical reception.)

While there’s been much talk about the governor’s plan to address teacher retention and recruitment through bonuses ranging from $5,000 to $15,000 per year, the critical point that has gone underappreciated throughout the whole process is the pitch is, at its core, a study.

While Dunleavy and Department of Education Commissioner Deena Bishop—a former school administrator who radically changed her tune on education policy once joining the Dunleavy administration—have claimed that increased school funding won’t accomplish anything, Bishop conceded at the hearing there’s also no definitive evidence that bonuses will actually work. Instead, she said, the plan is to study the impacts of the bonuses over three years (a period that also conveniently concludes after Dunleavy’s term in office).

“It is a study,” she said. “The feedback and empirical evidence on bonuses are split. I wouldn’t say it supports it one way or another … It is only a three-year pilot, and the funding is requested to span those three years so that we can take a look. Did we make any impact?”

At $60 million per year, it’s effectively a $180 million study.

Unsurprisingly, legislators are having a hard time justifying it when the state’s pinched budget means the money will likely come from the $174 million increase to annual school funding that legislators have already approved. At the hearing, Senate President Gary Stevens pointed this out, asking if legislators were wrong to try to improve the teaching profession with a dependable increase in school funding.

“Is the BSA the wrong way to increase teacher salaries?” he asked.

As has been the case with many of her appearances before the Legislature, Bishop gave a lengthy and meandering answer before conceding, “Certainly, I wouldn’t be able to answer that right now.”

Bishop’s vague claim that the BSA doesn’t flow through to teachers wasn’t received well by the committee, which includes Nikiski teacher Sen. Jesse Bjorkman. Bjorkman pointed out that the labor agreements already account for BSA increases, ensuring they’ll reach the classroom.

“When I see comments from people who should know better that money in the BSA doesn’t go to teachers, I wonder about those comments,” he said.

Bishop’s inability to answer questions about the study itself, who would conduct it, or what it would cost did not help the governor’s case, either.

As for the research, the committee also heard from Dr. Dayna Jean DeFeo, the director of ISER’s Center for Alaska Education Policy Research. She’s researched teacher compensation in Alaska and explained that researching bonuses is complicated because it’s hard to tease out how many people would have taken the job anyway.

“It’s complicated,” she said, adding that one attempt to run a statewide teacher bonus program in Massachusettes was scrapped after a couple of years.

She noted that research clearly shows that Alaska’s teacher compensation isn’t competitive nationally. While Alaska teachers are paid reasonably well — a point that conservatives frequently reference while opposing education increases — it doesn’t make up for Alaska’s high cost of living. She said that when you factor in the cost of living in Alaska, Alaska’s teacher wages are about 25% below the national average.

While DeFeo stopped short of telling legislators how to rework the program, she stressed that compensation isn’t the only issue driving turnover.

“Salary, benefits — that’s not the only thing driving teacher turnover,” she said. “Working conditions matter, too, and if we can improve working conditions, teachers will stay longer, even if we hold salaries constant.”

That was a point echoed in much of the public testimony the committee heard on Wednesday from teachers around the state. Many said that while they supported additional pay, they didn’t believe this would solve the problems driving teachers to leave Alaska. One said the governor’s proposed bonuses are being discussed as “moving money” among teachers.

“You could double my pay on the Titanic, and it wouldn’t help a lot,” said Juneau music teacher Michael Bucy, explaining his passion has been sabotaged by cuts that have ballooned his classes with students who would be better suited for courses that are no longer offered. “I don’t want to teach on the Titanic.”

Many teachers pointed out that the bonus program’s cost — more than $60 million annually — is more expensive than re-instituting a defined benefit pension plan for public employees, less than $50 million annually. As many pointed out, pensions rank higher on the state’s teacher survey than bonuses, largely because Alaska public employees are only eligible for a 401(k)-style retirement plan and not Social Security.

“I would love a bonus, but I need a pension,” said Natasha Graham, a teacher at Service High School in Anchorage.

Retired teacher Julianna Armstrong also testified against the bill, noting that the quality of her life and retirement is all thanks to the pension guaranteed to her by the state—the same kind that Dunleavy currently enjoys. She said you don’t get that kind of security with bonuses.

“Thanks to that promise Alaska made to me, I have a life, a home, and health insurance … I could not have this life if I had been offered lump sum payments,” she said. “Giving out occasional bribes is treating educators like naive children. ‘Look down all that money in your hand; don’t look in the distance at your empty future.’ The lump sum payment is a lump of coal. You can’t grow old depending on it.”

A hearing on charter changes was also held last Monday, and it followed many of the same themes as the hearing on bonuses: The reality is more complicated and nuanced than Dunleavy has asserted, and the solutions need to be more than a simple consolidation of power in the governor’s hands.

The Senate Education Committee heard from several local charter school programs, with the common note being that their connection and accountability to their local communities is a fundamental piece of their success. Putting the creation of charters in the hands of the Board of Education—whose most notable recent action was limiting how trans students can participate in high school sports—would not just eliminate that connection but create animosity between charters and local districts.

The message: Don’t fix what isn’t broken.

What’s next

It’s not clear what will happen next. If the governor vetoes the legislation, it will test several Republicans’ intestinal fortitude. It will take 40 legislators to override a veto of the education bill, which means at least some House Republicans would have to defy the governor and support a bill they voted for. So far, during this session, it seems they’ve been more willing to abandon their positions than buck the governor, but a weekend of town halls filled with education supporters is also hard to ignore.

Even if we get an override of the education bill veto, there’s still the matter of funding the bill. The governor has even more power there, with 45 votes needed to overturn a budget veto.

The Alaska Memo by Matt Buxton is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

‘A little disingenuous’

The Alaska Legislature is set to meet in a joint session on Tuesday to decide the fate of a dozen executive orders issued by Gov. Mike Dunleavy at the start of the session, and even some Dunleavy-friendly Republicans are pointing out the flaws.

The executive orders seek to eliminate several state boards and consolidate power in the governor’s office by granting department heads new powers or eliminating legislative input on board composition. According to a report by the Alaska Beacon, the slate accounts for one of the most expansive uses of executive order powers in state history, accounting for about 10% of all executive orders issued since statehood and equal to all executive orders issued in the past 20 years.

The orders will go into effect later this month unless a majority of legislators disapprove them via a vote at Tuesday’s floor session. The 31-vote threshold also gives an advantage to the typically aligned 16-member bipartisan House Minority and 17-member bipartisan Senate Majority.

The Legislature has already requested that the governor withdraw three executive orders, eliminating the Board of Direct Entry Midwives, eliminating the Board of Massage Therapists, and dividing the board governing the Alaska Energy Authority and the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority. If the governor doesn’t relent on those issues, they’ll be put up for votes on Tuesday, along with six executive orders already planned for a vote. The final three measures are not currently slated for a vote but could be brought up by any member.

One of the proposals garnering the most attention would reorganize the Alaska Marine Highway Operations Board, an advisory group created in 2021 to assist the state with the ferry system. Under state law, two of its members are appointed by the heads of the House and Senate, but Dunleavy’s executive order would remove them from the process and make all appointments at his discretion.

While Republicans have been generally willing to do the governor’s bidding, ceding power to the executive is a tough pill to swallow.

The governor’s administration has offered varying explanations for the move. On the legal end, the Department of Law has argued that it violates the separation of powers for the Legislature to appoint members to an executive board even though its primary purpose is advisory. On the policy end, officials have also complained that they’ve been unable to control the members appointed by the Legislature and that the board would work more effectively if everyone had to answer to the governor.

However, as far-right Rep. Sarah Vance, R-Homer, pointed out at a House Transportation Committee hearing last week, much of the explanation rings hollow when Dunleavy signed the bill creating the board in 2021.

“I’d like to note for the record that this same governor signed the bill, thus agreeing with the creation of this board as written in statute,” she said. “So, I find there to be a conflict with now wanting to say, ‘No, you can’t have the legislative appointees on there, and they should only be appointed by me’ … The bigger question here, if this is such a pressing concern, is why this was not brought up when the bill was originally before the governor?”

She called the explanations “disingenuous.”

Department of Transportation legislative liaison Andy Mills claimed that the apparent constitutional issues were known back in 2021 but that the governor allowed it to become law anyway. He said it didn’t become a problem until a few years later when the legislative members who “have no ability for us to have some say over” didn’t meet the governor’s expectations.

Several legislators who worked closely on that bill say that having differing and sometimes conflicting views on the board is precisely the point. Rep. Louise Stutes, a Kodiak Republican who caucuses with the bipartisan House Minority and sponsored the bill creating the board, said she was troubled by the governor’s justification.

“It alarms me to hear you say, ‘We have no control over these board members.’ My opinion is you don’t want a board where everybody thinks the same,” Stutes said. “You need a board that has different ideas.”

Stay tuned.

The Alaska Memo by Matt Buxton is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Alaska Memo Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.