Unpacking the Alaska Supreme Court's decision on redistricting

There's plenty of notes for the next round of redistricting... in 2031.

Good evening, Alaska!

In this edition: Let’s unpack the big takeaways from the Alaska Supreme Court’s decision on redistricting; including what it means for the state’s legislative districts; and what it means in the long-term for redistricting.

Spice level: 😷

Who’s in: Today, we can add former North Pole Republican Sen. John Coghill and 2020 U.S. Senate candidate Al Gross, an independent, to the list. As I've been reminded after Friday’s wild speculation edition, there were five people who’ve already officially filed to run. They include undeclared candidate Gregg Brelsford, nonpartisan candidate Bill Hibler, Republican candidate Bob Lyons, Libertarian candidate J.R. Myers and Republican candidate Stephen Wright.

Unpacking the redistricting decision

A week ahead of its deadline, the Alaska Supreme Court issued its ruling on the Alaska Redistricting trial on Friday afternoon. In expected fashion, the ruling is short and to the point delivering rulings on the key issues around the state’s legislative districts ahead of the June 1 filing deadline. A fuller ruling is expected at a later date, but there’s some interesting takeaways from the ruling. But first, the big impacts:

AFFIRMS the ruling that the East Anchorage Senate pairings were, in fact, a political gerrymander that violated Alaska’s equal protection clause, requiring that they be redone.

REVERSES the ruling that found the Skagway/Juneau maps were invalid because the board failed to take a “hard look” at the public testimony that suggested a different layout, meaning the maps can stay the way the board drew them.

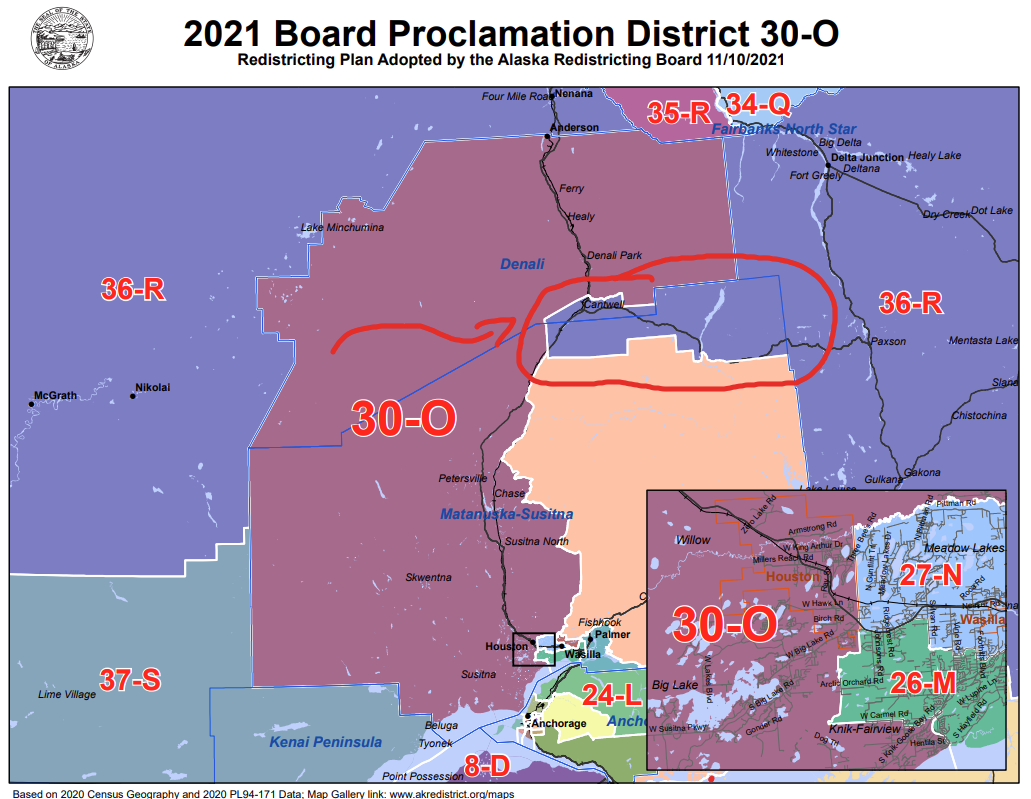

AFFIRMS, mostly, the ruling that found the Mat-Su and Valdez maps were constitutional. It REVERSES the decision that found the so-called Cantwell Carveout was constitutional, meaning it needs to be returned to the Denali Borough from the rural Interior district. Pictured here:

Looking ahead, we’ll still have to wait and see what the Alaska Redistricting Board does in terms of revising the Senate pairings but unless they try for something really wild, then it’s likely that Eagle River’s House districts will be consolidated—if for nothing else but a practical matter—while the rest of the map could be up in the air. While most proposals would put the two East Anchorage seats together, nothing requires them to be put together. Politically speaking, it’s going to have a big impact on Anchorage’s legislative representation and likely will move a few Senate seats into the competitive column from a solid Republican (like the East Anchorage/Eagle River pairing was). It’s also likely to have a big impact on the decisions about who runs for what given that it could separate potential Senate candidates in some cases while pairing some together in others, complicating their path to victory.

In the long-term

And now for the wonky stuff: What this means for redistricting in the future.

The “Hard Look” standard no more

Much of Superior Court Judge Thomas Matthews’ ruling had revolved around the role that public testimony plays in the redistricting process, specifically the “hard look” standard borrowed from federal litigation that argues the board should at least give some consideration to public input. That doesn’t appear to have carried water with Alaska Supreme Court. While the justices don’t specifically say it doesn’t have merits, they say the maps in the Skagway/Juneau case met the constitutional requirements and “should not otherwise be vacated due to procedural aspects of the board’s work.”

If let stand, it would have required the board at least take a “hard look” at concerns raised during the public testimony part of the process and at least come up with a justification for why the Alaska Constitution’s redistricting requirements prevented them from following that input. The board had argued that it would upend the process and turn public testimony into a political game, a point that one justice brought up during the oral arguments. In reality, it was never much more than an additional hoop for the board to jump through. That’s because just what would satisfy that “hard look” was pretty broad and if it had gone back to the Alaska Redistricting Board under these standards, it’s not impossible to see how they’d come back with the same results just with better justification this time.

Instead, the ruling delivered by the Alaska Supreme Court is ultimately much more firm in its handling of the East Anchorage Senate pairings. Here, there’s no process issue that can be fixed by going through the motions of a “hard look.” Instead, the Alaska Supreme Court has ruled that the East Anchorage Senate pairings are, in fact, a political gerrymander that violates the equal protection clause of the Alaska Constitution. There’s no amount of new meetings or documents that can erase that.

Why it matters: While it seems like it’s a loss for the public input, we ought to be clear that the board would’ve likely found a way to skirt it in the future. If there’s one big takeaway from following this whole saga, then it’s the board is getting really good at breaking the rules without breaking actually breaking the rules. They knew full well just how much latitude the process grants them and bent it to the extreme. There’s no guarantee that the “hard look” standard would have been a defense against creative legal thinking in the future, which is probably why no one spent a great amount of time or effort defending it in front of the justices.

Political gerrymandering IS possible

What is a far more consequential outcome of the ruling is the affirmation that, yes, the courts can do something about political gerrymandering. That’s at the heart of the justices’ decision to affirm the lower court’s ruling that the East Anchorage Senate pairings were an unconstitutional violation of East Anchorage voters’ equal protection and that it was a political partisan gerrymander. That alone is significant but will be really important is just what level of evidence they require to find something is a political gerrymander.

The Alaska Redistricting Board argued anything short of a full declaration of intent cannot be reviewed by the courts. The East Anchorage plaintiffs argued that gerrymandering and racism are much easier to conceal and argued that you should be able to infer intent rather than having an explicit declaration. In this case, of course, they did have about as close as you’ll ever get to a full declaration of intent to gerrymander board member Bethany Marcum’s statement that the plan would give Eagle River more representation. The board attempted to invent an explanation for that statement after the fact, noting that she would have said the same thing for East Anchorage because it was being split into three Senate districts. At trial, the board’s attorney tried to defend the plan by arguing East Anchorage with its three different senators would have a “head start” on getting its goals met in the Legislature.

Not only was that logic hard to swallow on its own—after all, the idea of splitting an area off into various different districts has its own gerrymandering term of “cracking”—and the justices let the board know that much during trial, but there’s evidence in the record that undermined the board’s arguments. In the Valdez trial, the witnesses there testified at length about how their Senator—Wasilla Republican Sen. Mike Shower—had never visited their community and never took their meetings during the legislative session.

Why it matters: It’ll really matter just what evidence the Alaska Supreme Court saw that led to the ruling that there was a political gerrymander. It’s possible that they looked at just Marcum’s statement—which the justices brought up on their own—and saw that as clear evidence, but whether they saw it more as an inference of gerrymandering will be important for future plans. If it’s the former, then future redistricting boards will need to be more careful about what they say on the record. If it’s the latter, then that could lead to truly stronger protections against gerrymandering in the future.

Reconsidering priorities

The sprawling nature of the lawsuits ended up mattering in other places, too. One point raised by several of the litigants was that the board inconsistently applied its standards to the cases. The Alaska Supreme Court agreed, noting that the board had prioritized socioeconomic integration over compactness in the case of the Cantwell Carveout—their decision to carve Cantwell out of the Denali Borough to place them with the rural Interior district—but did the exact opposite with the Juneau/Skagway maps. The court even referenced this in its decision ordering the board to eliminate the Cantwell Carveout.

While not before the court in this case, Senior Justice Eastaugh wrote a concurring opinion that flagged a potential issue with how the Alaska Supreme Court has weighed the constitutional requirements of contiguity, compactness, socioeconomic integration and population deviation:

“I write separately because I have doubts about whether Hickel v. Southeast Conference correctly described the priorities for applying the contiguity, compactness and socio-economic integration criteria. If I were reading the constitution in a vacuum, I would not necessarily conclude that the delegates agreed or that the Alaska Constitution’s text requires the first to criteria should have priority over the third. But there was no challenge to Hickel’s description of those priorities in this case, nor any contention its description should not be given stare decisis effect. Moreover, my doubts to not affect any of these petitions, even as to the ‘Cantwell Appendage,’ because the asserted increase in socio-economic integration in House District 36 does not outweigh the diminution in that district’s compactness.”

Why it matters: As Justice Eastaugh writes, the issue of priorities isn’t at stake in this trial and would not have made a difference in his eyes. However, this statement is something to keep in mind for the next round of redistricting… in a decade.

Not addressed

The decision here doesn’t directly address a handful of other issues that were brought up during the appeals. None were of direct importance to the task of redrawing the maps to comply with the ruling, but they could also have long-term impacts:

- What weight do the ANCSA boundaries carry in the redistricting process? The board certainly elevated them to a similar level as municipal boundaries, which serve largely as an indicator of socioeconomic integration. At the very least, the Alaska Supreme Court did not find that disqualified the plan but it’s not clear what weight, if any, they’re due under the law.

- What about the Open Meetings Act violations? Judge Matthews ruled that the board had violated the public trust throughout in what he called a secretive process. He also raised concerns about the board’s overuse of executive sessions and attorney client privilege to shield many of the policy decisions from the public view. The Board, meanwhile, has argued that it should not be subject to the Open Meetings Act… even though it was adopted by the board.

The Alaska Memo Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.